DraftDiagnosis: A Comprehensive Q&A

Back in July, Voicebrook announced the launch of DraftDiagnosis, a groundbreaking generative AI feature designed to revolutionize how pathologists...

3 min read

Voicebrook Friday January 29, 2021

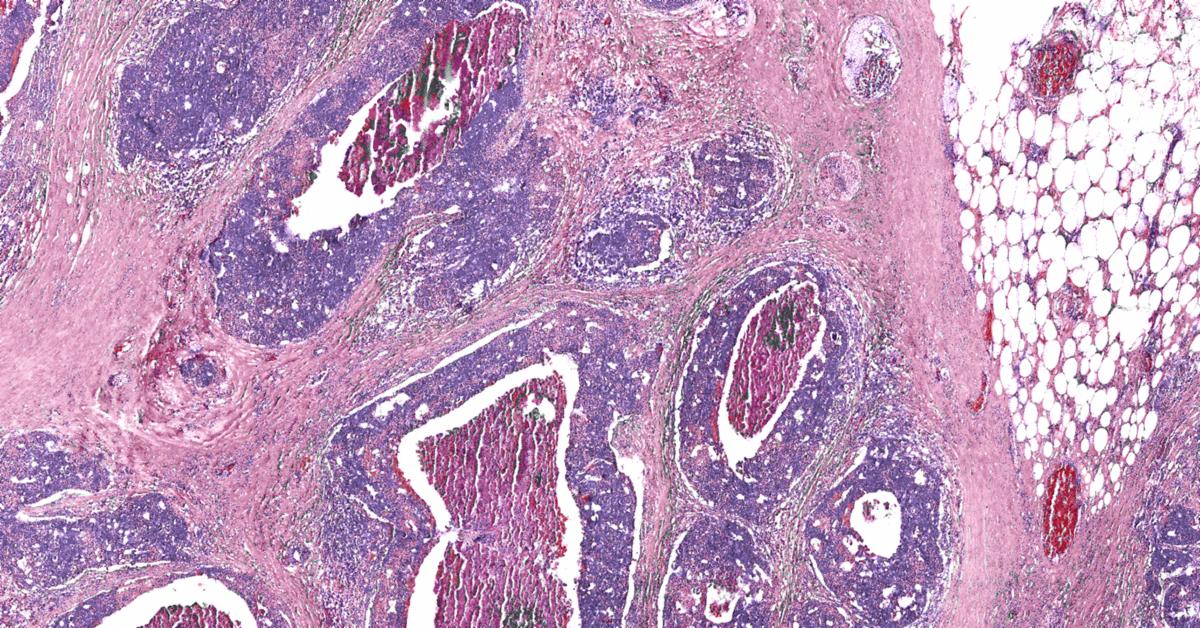

January is Cervical Health Awareness Month. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, but the incidence of cervical cancer has rapidly declined in the United States in recent decades, largely because of widespread screening practices that were initiated in the 1950s.

Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control.

Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control.

The most well-known and successful screening tool is the routine Pap test, a procedure that collects cells from the cervix. Those cells are examined in the cytopathology lab for cancerous and pre-cancerous cells. Because cervical cancer usually doesn’t cause symptoms until its later stages, it's essential to spot it early—and take steps to prevent it from ever starting.

The proof is in the numbers: since the inception of the Pap test, cervical cancer has gone from the number one cause of cancer death in women to number 15. Deaths from cervical cancer have been reduced by about 70 percent. And yet, last summer the American Cancer Society (ACS) released new guidelines that seek to phase out the use of the Pap test, in favor of testing for HPV (human papillomavirus).

HPV is spread through sexual contact, and it’s a common infection. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), nearly everyone will get at least one type of HPV over their lifetimes (men and women alike). There are multiple strains of HPV, and only a small number have been linked to the cellular changes associated with cervical cancer. The CDC says nearly all cases of cervical cancer are linked to HPV infections.

That’s why, in recent years, cotesting has become more popular, in which both the HPV test and the Pap test are paired as screening tools. The HPV test looks for the high-risk types of HPV that are more likely to cause pre-cancers and cancers of the cervix.

Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control.

The new ACS guidelines recommend that cervical cancer screening should begin in average‐risk individuals at age 25 and cease at age 65, and that the preferred strategy for regular screening is primary HPV testing every 5 years. They note that these guidelines are making a move away from traditional cytology testing toward HPV testing.

This shift has caused concern among cytologists and the College of American Pathologists (CAP). In the January 2021 issue of CAP Today Magazine, an article by author Anne Paxton notes that, “The CAP, however, believes that the ACS recommendation poses significant risk to patients and gives short shrift to cotesting, which the CAP said in an Oct. 15 letter to the ACS should be continued as a screening strategy because it provides the sensitivity and specificity needed for all patients.”

Paxton writes that one of the CAP’s main objections to the ACS guidelines—and an obstacle to their quick widespread adoption—is that fewer than half of laboratories in the U.S. perform primary HPV testing with the only two FDA-approved tests available.

The CAP Foundation will fund 14 See, Test & Treat program host sites in 2021, providing access to free cervical and breast cancer screenings. Image courtesy of CAP.

The CAP Today article also quotes Dr. Diane Davey, who practices pathology at the Orlando Veterans Affairs Medical Center and is a professor of pathology and associate dean at the University of Central Florida. “There is definitely still a significant portion of the population that is not getting regular screening and those are some of the women who are still getting cervical cancer,” Dr. Davey told CAP Today. With the level of false-negatives HPV testing has, even though the test is considered very sensitive, “we are concerned that maybe the HPV test is missing something in women undergoing infrequent screening.”

Other pathologists agree. “As a pathologist with more than a decade of experience, I am concerned that these guidelines do not fit with real-world screening within the U.S. healthcare system,” said Dr. Carrie Chenault. “To exclude women under 25 from getting a simple test that has saved countless lives feels completely counterintuitive. That’s especially true at a time when there is absolutely not enough preventive care happening in the U.S., and the Pap test stands as one of the greatest successes in the history of preventive health. Why do young women in their early 20s not matter anymore?”

Dr. Chenault says in her pathology career, she has seen seen HPV-negative cancers when reviewing cytology slides. “Taking away the Pap test will only increase the chances that disease will be missed, and that women will be put at greater risk. Serious consideration must be given to the fact that the Pap test can also help detect infections and other asymptomatic cancers that may not be diagnosed otherwise.”

Dr. Dina Mody, director of cytology laboratories at Houston Methodist Hospital and a former chair of the CAP Cytopathology Committee, noted similar concerns to CAP Today. Dr. Mody said that at Houston Methodist and BioReference Laboratories, they spotted some concerning trends when they had a big uptick in cotesting. “We noticed as early as 2013 that there were cases of high grades and cancers that were testing negative with the HPV test. And we weren’t the only ones noticing that,” Dr. Mody said.

But the ACS Guideline Development Group (GDG) maintains that, compared with primary HPV testing, cytology testing—the former mainstay of cervical cancer screening—”has inferior sensitivity and provides lesser assurance regarding future risk. The combination of cytology and HPV testing (cotesting) offers very little incremental benefit in detection but increases the number of procedures and the risk for harms. Therefore, the GDG concluded that primary HPV testing should be designated as the preferred screening test.”

These guidelines are to be phased in over time, but that timeline has yet to be determined. Gynecology organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have not yet adopted the ACS recommendations. In the interim, doctors say there are other ways to proactively prevent cervical cancer. These include limiting exposure to sexually-transmitted HPV infections, communicating with doctors about all available cervical screenings, avoiding cigarettes, and getting the HPV vaccine if under the age of 26, which protects against the HPV strains that cause most cervical cancers.

Back in July, Voicebrook announced the launch of DraftDiagnosis, a groundbreaking generative AI feature designed to revolutionize how pathologists...

Medical laboratories are intrinsic to the ultimate well-being of patients everywhere. That's never been more evident than now, during our current...

CAP Annual Meeting Going Virtual Every year, pathologists come together as friends and colleagues at the College of American Pathologists'...